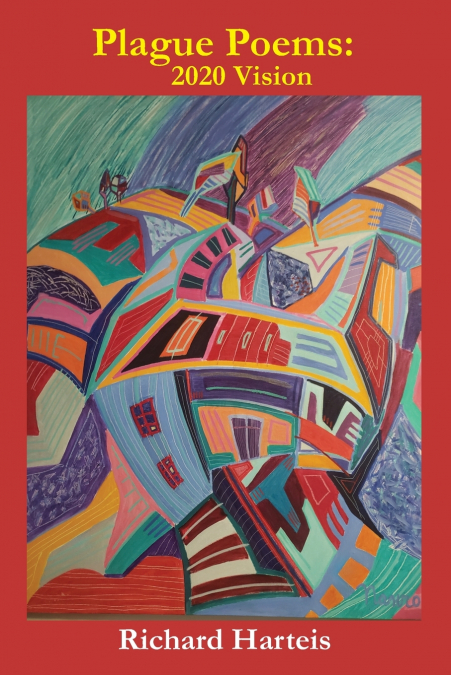

Richard Harteis

'It ain’t over ’til it’s over,' I believe the great Yogi said. To which someoneadded, 'yeah but when it’s over, it’s over.' Well who knows what the futurewill bring? Que sera sera. We may be facing a very dark winter as in Gameof Thrones, or we will see the death of this virus at the kind hands of naturewho so unkindly delivered it to us in 2020.Like other artists in this pandemic I have struggled to come to terms withall the new burdens it has brought us: masks, social distancing, shortages,less than truthful politicians and scientists, loneliness, fear, sexual frustrationand the sad irony of putting all this in the context of a beautiful spring andcreatures not knowing the world has changed. A woodpecker rat tat tappingon a tree in the forest for his breakfast, puffs of daisy seeds flowing on thebreeze, the sun so warm, the grass so green and fresh. Robins, titmouse,and tiny hummingbirds miraculously making their way across the Gulf fora little bit of sugar water in burgeoning blossoms.It is a world Camus first looked at in his book THE PLAGUE and another,THE STRANGER. His words become prologue and epilogue to myown observations, and in the middle of all of this so far, the season of Easterwith its promise of resurrection and transformation. Love, amusement, hopeand just training your mind to observe what the world has become and whatit may yet be, the opportunities Camus first looked at in his plague and laterthe stranger.One happy result of this artistic thrashing about has been the chance toreconnect with old friends such as Pancho Malenzanov who painted his villagein the middle of a hurricane which seems appropriate for the cover ofthis particular book. I divided the book into four parts, somewhat arbitrarily beginning with Pandemic; then Play including occasional observations and attempts at humor; then Roommate, since when you’re living with someone youget to learn a lot about them; and-finally-Easter with prayers to help us see the light. 'Covid Casualty' is a sad reflection on the aftermath of living in lockdown with someone you love, a drama which has played out in any numberof households as the isolation and forced togetherness takes its toll. A sacrilege perhaps to compare the suffocation of a room mate who could notbreathe to that of George Floyd dying at the hands of a cruel fellow humanbeing, and the global uproar fueled by the frustrations of isolation. A singlepoem serves as an epilogue, since its rather bleak assessment does not reallysuit for the section titled Easter. Still, as an indictment indictment of capitalpunishment, it seems an appropriate vision of Camus’ humanism, his compassion for the human predicament to end with. As da Vinci has said 'it isan infinitely atrocious act to take away the life of a man.' This is what thevirus has done atrociously in thousands of cases now. These poems meannothing if they forget those thousands who in desperation and courage haveachieved their own death. The collection ends with a final image of hopeand resurrection, a last final word. Even when its roots are in the dirtiest waters, the lotus produces the most beautiful flower, an ancient symbol of rebirth, purity and self regeneration. It calls for spiritual enlightenment sodirely needed in these troubling times when all life is threatened.